I've posted about Mary Sue before, and feminist anachronism in historical fiction, but this morning I was cruising one of my fora and ran into a thread about what tropes would you throw in the bin, as a histfic reader? Apart from the "Dark Ages = Land of the Stupids" dirty Barbarian foolishness, a clear winner in this discussion was the presence, in so much historical fiction, of the modern, BEAUTIFUL, feminist heroine main character. Ugh/sigh.

One poster said,

But . . . it seems like every young woman in every historical novel doesn't want to get married and just wants to be "free" (to do [I]what [/I]for the rest of her life?). I would like to see a real examination of the other young women who made the best of things.

I responded:

In my first novel, there are two significant marriages, and two scenes involving the prospective brides' acceptance of their arrangements. In the first case, I wrote the character as seeing her marriage as a sort of dynastic opportunity - a role to which she not only had been raised, but had aspired personally. She is eager to fulfill a certain type of feminine glory, queen to a great husband, and she sees a clear potential to become mother of a dynasty. The second case is a more prominent character, who comes to her marriage out of faith, a sense of fate, and a certain amount of attraction to both the role and the husband. The relationship is developed pretty deeply, and is loving, difficult, committed in a way modern people don't always understand, and fruitful (also in a way modern people don't always understand).

In the WIP, the main character is a princess who is ... physically uncompelling. She cultivates her intellect and personality, and she also uses her position to make up for the idea that those around her find her ugly. She marries very young and against all the rules, and watches her husband pay for this sin. She seeks power through the channels available to her, and eventually herself pays for her heterodoxy, pride, and ambition. (Her story, by the way, is not fictional.)

***

In one of those moments which can be a bit too on-the-nose "meta" to tolerate (but which I hope I handled well), I wrote this:

Cholwig gave me back a smile as we slowed near the threshold of the hall. “I think a woman submits to her lord, and power is in the eye of the beholder. It is possible marrying a king is more servitude than success. Do you remember the old way a tribe might attack the Empire, when Rome was strong? A small king would say, ‘we’ll attack Rome, and surrender, to be absorbed into its protection and wealth, and that way, the people will prosper’.” He regarded me for a moment. “A woman can do the same. Make a sally at a formidable man, a king. And, in surrender, wage peace of a comfortable nature.”

The military strategy is a historically documented one - and, in fact, not exclusive to the Empire in Rome. Just recently, I ran across a film from I believe the 1960s or thereabouts, in which a fictional, tiny European nation was going to pick a war to lose, either with the US or perhaps the British Empire, for precisely the same reason.

It seems to me extremely likely the strategy, with women, was a real one as well - shoot, though we hate to admit it, there are *today* still plenty of women and girls raised on the idea of men-as-providers, who look to relationships this way. Not necessarily gold-digging, but certainly a tendency to mercenary gender relations is not a thing of the past completely. I know plenty of women who have never lived on their own financial terms, and have never intended to. My autonomy may not be the anomaly it once was, but it's still not standard for women either.

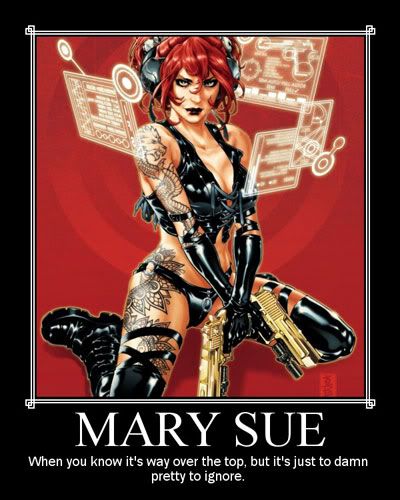

The thing about Mary Sue is this: once upon a time and not so long ago (cue Bon Jovi, for those who are hating me right now), she was an innovation. I have to forgive the temptation to write her. Women authors may use her as an avatar to be glamorous, rich, and sexy to everyone on feet - but it hasn't been long since Mary actually had something to say. When you think about how many centuries literature endured under the yoke of systematized oppressions for us ALL (not just women), it's hardly surprising that writers in the 20th century began breaking out magical characteristics - and, given the 20th century in much of Western, and particularly American, culture, it's less surprising still all the main characters had to be supernaturally endowed with superior characteristics, and not least of these was sex appeal.

It's tiresome now, but when you look at the reasons Mary Sues sprang up, the bumper crop she became is easy to understand.

It's also easy to understand why people are so judgmental now. It's been JUST long enough in literary time, and perhaps eons worth of time in millenial insta-news-cycle/short attention span terms, the backlash is just as obvious as the initial popularity was. When "Mists of Avalon" came out, the character of Morgaine was groundbreaking. She spawned copies, and a more general trend, and looking backward maybe she looks like a Mary Sue too - modern humanist/liberal morality, femininity, beauty, the whole package. But like many early iterations of what become larger phenomena, Morgaine had more depth than perhaps later, more watered-down examples would carry. And Morgaine was a teaching tool.

Cry about Mary Sue as we will, she apparently has taught a lot of readers ... *something* ...

So my resistance isn't to the forces and the motivations that gave us Mary Sue in the first place. It's to the weak tool she has become - it's to the subversion of a feminist point-making into a plethora of pneumatic, gorgeous, goddesses (though I'll never stop blessing Michelle Brower for coming up with the genuinely insightful analysis of urban fantasy heroines' changing roles, in her comment, "the boobs are getting smaller"). It's to the easy-way-out insertion of modern feminism and attitudes onto characters who, in all fairness, could never have even developed some of "our" ways of thinking - never mind enacted them. It's to the injustice, of ignoring the real obstacles and opportunities ANYone (again, not just women - but, yeah, particularly women) had, the real context of history, whatever a given period.

Sure, we're all fascinated by those who fought against a given system - there are reasons books about feisty medieval women do sell, and we can hardly pretend Aliaenor of Aquitaine (kids, that's Eleanor to your modern spellin'-style) was a dainty little thing. It's perhaps unjust to pretend all women were shrinking violets, in a similar way it's dangerous to pretend none of them were.

But that is just what chafes me as an author. Characters don't exist outside their time - but they also don't exist in the prejudicially-defined prisons modern judgment presumes "the past" had to offer, depending on era. The Middle Ages (ugh, what a nicely imprecise term - you should see the wildly erratic definitions people have for it) wasn't all about wimples and tiny rosebud mouths, any more than the 19th century was all about consumptive milquetoasts nor hookers-with-hearts-of-gold, any more than the Dark Ages were summed up in Boudicca, nor Rome by Valeria Messalina ... OR Cornelia the Mother of the Gracchi.

Characters need to be about more than just their context, whether we choose to manipulate the context or not. Write to them - not to a didactic point, nor to a stifling set of assumptions or required set of actions. If they're honest, they should fit. Wherever we end up putting them.

No comments:

Post a Comment